The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics

A Chance Encounter

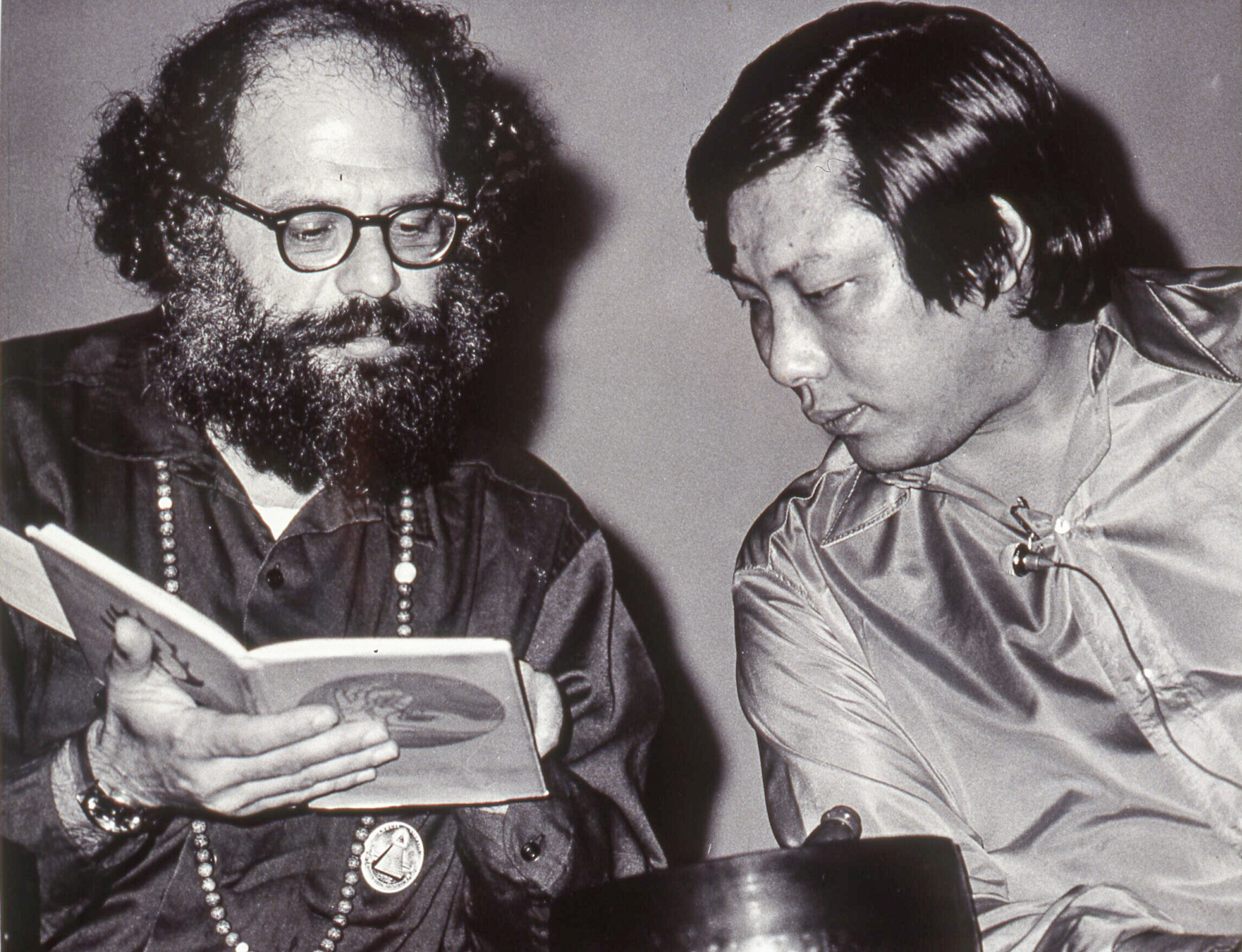

The origin story begins on the streets of New York City in 1970 when Allen Ginsberg tried to “steal” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s cab, and the rest, as they say, is history. They ended up sharing the ride, and the two had an instant spark that quickly developed into a profound creative and spiritual relationship. Ginsberg introduced Trungpa Rinpoche to many prominent, cutting-edge poets of the time, especially those connected to the Beat literary movement. Fast forward four years to the first session of Naropa University (then Institute) in the summer of 1974, and Chögyam Trungpa invited many of these counterculture and experimental writers to Boulder, Colorado, where inspiration ignited, and the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics was born.

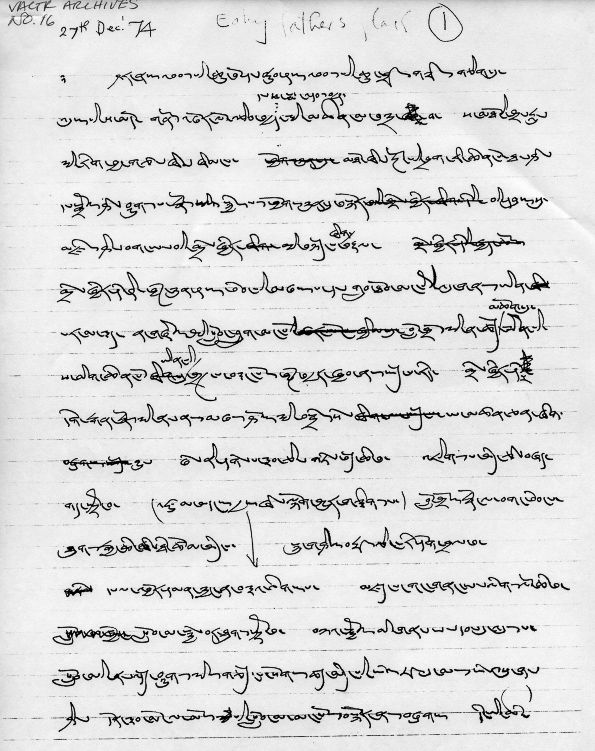

As Naropa Institute’s founder, Trungpa Rinpoche’s aspiration for the poetics department was a sort of creative and spiritual cross-training: making Buddhists better communicators and teachers through the study of poetry, and uplifting poets to be more beneficial to others through the practice of meditation. The department was especially close to Chögyam Trungpa’s heart, because he was a great poet himself — trained from a young age in Tibet and a master of traditional Tibetan forms, who, by the sixties, was also writing unprecedented English free verse.

Experimental Poetics Hotspot

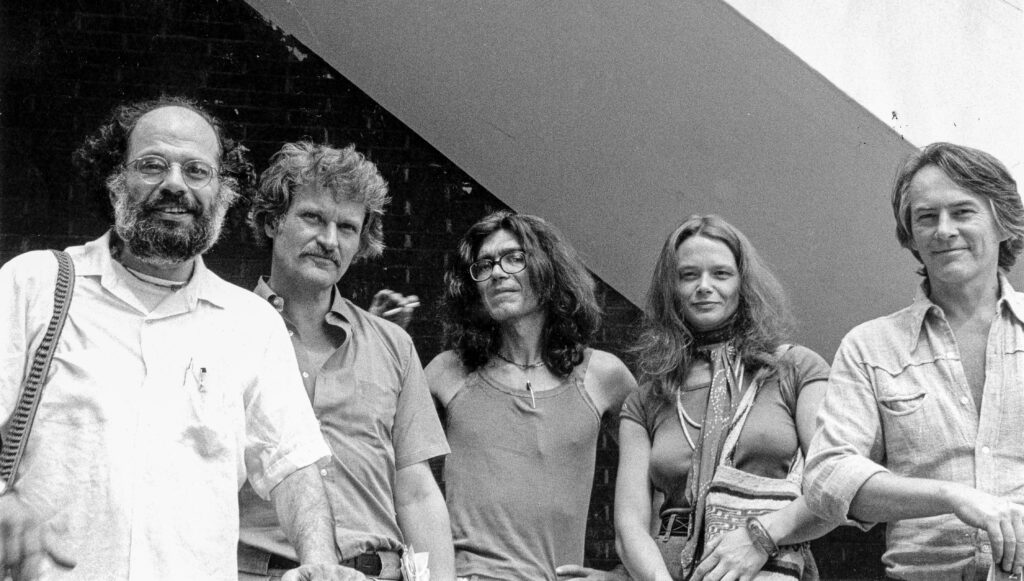

This Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics was co-founded by Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman. Ginsberg was a legendary poet and central figure of the Beat Generation who had shaken America with his epic poem “Howl,” first read in 1955 in San Francisco, with Jack Kerouac in the audience. Anne Waldman was and is a luminary poet in the Outrider experimental poetry movement, coming from the lineages of Beat, New York School, and Black Mountain, and is known internationally for her powerful performances. She is currently still the Director of Naropa’s Summer Writing Program. Waldman, who was interviewed for this article, explains the unique environment that drew so many illustrious writers: “It was founded with the Beat ethos of wild mind, spontaneity improv, and [hosted] Beat guests, but many of the guest writers also were familiar with, and trained in other wings of the New American Poetry, which included Black Mountain College, New York School (Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery), San Francisco Renaissance, and the Black Arts [Movement].” The impressive and long list of writers who taught and/or read at the Jack Kerouac School includes: William Burroughs, Amiri Baraka, W.S. Merwin, Joanne Kyger, John Ashbery, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Diane di Prima, Philip Whalen, Gary Snyder, Sonia Sanchez, Jackson MacLow, Bernadette Mayer, Miguel Algerin, Ken Kesey, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Gregory Corso, and many, many more.

Buddhism Meets Poetics

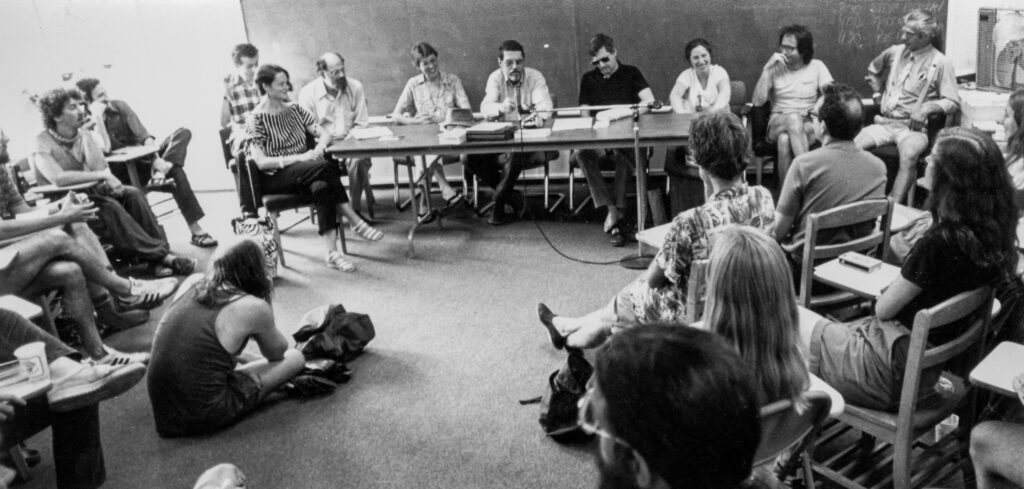

Naropa Institute was the first Buddhist-inspired university in the West, and within it, the Jack Kerouac School was also a first in bringing together the study of Buddhism and poetry at the nexus of mindfulness. This connection is clearly articulated in the school’s 1974 mission statement: “There being no party line but mindfulness of thought and language itself, no conflict need arise between religion and poetry.” With this core value, students studied more than solely Buddhist poetry, such as Japanese haiku or tantric dohas, nor was the curriculum dedicated exclusively to Beat poets and writers. Instead, the department had a wider emphasis on Eastern and Western spontaneous composition, as well as writing reflecting the author’s awareness of their own mind. There were classes in the Modernists James Joyce, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound. Ginsberg taught from the Norton Anthology of English Literature, and Waldman from the international anthology Technicians of the Sacred. There was also a small rotating Shakespeare summer session.

A Founders Poetry Reading

In August 1975, the school hosted a poetry reading for a crowd of over eight hundred people, which featured Anne Waldman, Allen Ginsberg, and Chögyam Trungpa. The event was filmed, and forty-seven years later, this footage is now in the Chögyam Trungpa Digital Library (which you can view with an interactive transcript). This recording is more than a performance from three great poets. It was three ground-breaking poets who had a profound influence on each other’s work and changed the trajectory of each other’s writing careers. They were also a Buddhist teacher and his students, and close friends. As the only one still alive, Waldman shares what these events meant to her. “I was always excited to read with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and try out new poems… We weren’t together at Naropa by accident or simply invitation, but more of an occasion of ‘tendrel’, or auspicious coincidence.”

Influence and Inspiration

During the reading, Trungpa Rinpoche expresses gratitude for the influence that Ginsberg and Waldman have had on his latest poetry, a couple of times pointing to specific poems. In his introductory remarks, he describes his journey from his Tibetan poetry roots to his latest English free verse work as an “Americanization” in a positive sense. It’s an Americanization not in the usual colonial or cheapening meaning, but as a welcome change — as he says, “taking a leap rather than corruption.” He credits his friends as having a lot of influence on this “breakthrough” — a radical shift to his own contemporary style. It’s also interesting to note that with all the credit he is giving to Waldman and Ginsberg, he’s careful to mention that he’s not throwing away his previous work — that the underpinning of “honesty, power, and energy” in his traditional Tibetan poetry is unshaken. It’s the style that has changed. This change in style may have been another of the many skillful means Chögyam Trungpa used to transmit the dharma to this particular generation of Americans he encountered. Allen Ginsberg was wildly famous; clearly many people in this counterculture era connected powerfully to his work (not to mention his major cultural influence on queer art, political activism, and other writers). Perhaps Trungpa Rinpoche decided to take this poetic leap to better communicate with these people.

While Ginsberg and Waldman were briefer in their poem introductions during this event, Chögyam Trungpa’s influence on them is obvious in the dharmic themes and language they use. Of note is Ginsberg’s recitation of his magnum opus “Howl,” which had been published almost two decades earlier in 1956. Here, it has been revised to include allusions like “holy Boulder” and “Book of the Dead.” The beginning of Waldman’s classic “Fast Speaking Woman” includes an unpublished invocation to “female deities, wrathful and compassionate.” (And if you’re particularly interested in any of these poets’ work, comparing their performance here with the later or earlier published version of the poem is an illuminating peek into their writing process.)

Chögyam Trungpa influenced both Ginsberg and Waldman in emphasizing shamatha meditation’s importance and relevance to writing, and they both ended up teaching meditation to students and to the larger Boulder community. Trungpa Rinpoche also pushed them towards more spontaneity in composition, putting them on the spot to compose poetry in his own signature fashion. “First thought, best thought” is a slogan that arose out of conversations between Ginsberg and Trungpa that encapsulated this kind of spontaneity — not referring to the literal first thought one has, but the first thought coming from a meditative state, or a fresh mind not bogged down by neurosis. (This is also the title of the 1983 poetry collection from Chögyam Trungpa that contains most of his poems from this reading.)

While Ginsberg and Waldman had spoken publicly and been interviewed extensively about their work, Trungpa Rinpoche had spoken only about his general approach to writing poetry and the larger journey of his poetic process, and commented very little on his specific poems. In this recording, he takes the time to introduce each poem, and we are given a rare glimpse of his inspiration and life at the time of writing. For instance, when introducing his first poem, “Victoria Memorial,” he tells a story of leaving heavily polluted Oxford where he was attending university, for an excursion to London. He describes how beholding the memorial at Buckingham Palace cured his culture shock-induced creative block, and it was shortly thereafter that he wrote his first poem in the West.

Poetry as Performance

Watching the video of this reading, you can experience Ginsberg and Waldman’s poetry as performance. Since both of them are very physical, throwing their whole bodies into their recitation, being able to watch and listen is to fully experience their work. Taking full-body breaths, Allen Ginsberg gestures, rocks back and forth on his cushion, and smiles to indicate irony. He sings the Prajnaparamita mantra from The Heart Sutra with his harmonium. Anne Waldman sways and bobs at the podium, her face expressive, her raw charisma drawing in the sea of people, which comes to an apex as she sings and chants her passionate mini-classic, “Fast Speaking Woman.”

If you have any interest in poetry, dharma art, or even only Trungpa Rinpoche’s work, this recording can’t be missed. It’s the closest you’re going to get to actually being there, short of time travel. Electric.

More Gems from the Digital Library

This featured poetry reading is just one of the recordings in the library’s poetry and poetics events. Other highlights from The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics are listed below.

- 1975 group poetry reading (poetry reading featured in article)

- Poets’ Colloquium (Trungpa Rinpoche, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Whalen, Waldman, Rome, W.S. Merwin, Corso, and others)

- Meditation and Poetics: Class Discussion (Chögyam Trungpa visits Allen Ginsberg’s poetry class)

- Dharma Poetics: Talk 1 (introduction to dharma poetics, includes spontaneous poetry by Trungpa Rinpoche and Ginsberg)

- There is also a group of recordings on “Art and Aesthetics”: teachings on dharma art, creative process, egolessness in artistic practice, symbolism, art in everyday life, and more.

Sources

Anne Waldman, email interview with author, September 24, 2022.

Bye, Reed. “The Founding Vision of Naropa University.” In Recalling Chögyam Trungpa. Edited by Fabrice Midal. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2005.

Ginsberg, Trungpa, and Waldman. “Poetry Reading: Anne Waldman, Allen Ginsberg, Trungpa Rinpoche” Video recording of poetry reading. 9 August 1975. Item 19750809VCTR1, Chögyam Trungpa Digital Library, Boulder, Colorado.

Waldman, Anne. “Tendrel: A Meeting of Minds.” In Recalling Chögyam Trungpa. Edited by Fabrice Midal. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2005.

Learn more

To learn more about Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, read his biography

To learn more about Anne Waldman and her work, visit her website

To explore Allen Ginsberg’s work and legacy, visit the allen ginsberg project

Read about the current programs at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University